The Impact of Nature on Dementia

Right before the spring of 2019, I was assigned the task of writing an article for the Penn Memory Center on the Philadelphia Flower Show. The reason we decided to feature the Flower Show was to highlight a display called “Promise Garden” featured that year.

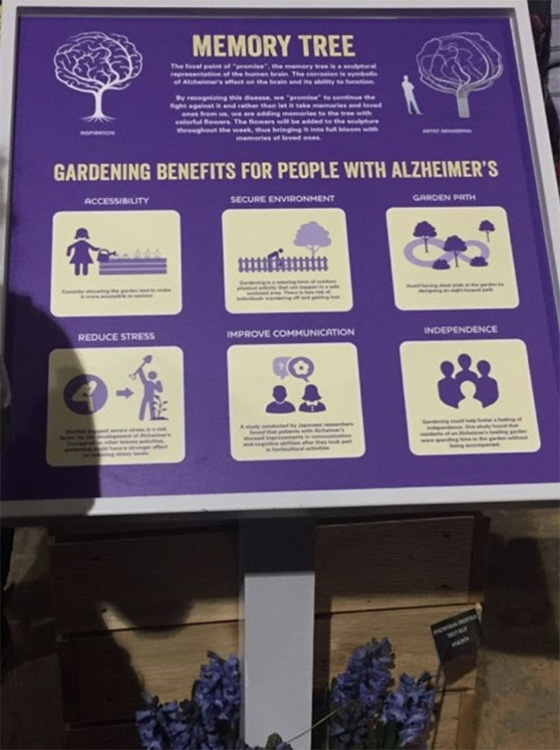

This display had “flower beds at a high perimeter, a circular path and no jarring shapes or colors” and “was designed for those with dementia as an area where one could not wander off, get lost, or experience stress.” This was the first time I ever thought about the relationship between nature and dementia.

Gardening was one of my best friend’s and her grandmother’s favorite pastimes, only second to preparing meals together with their family. They had a small plot of land, a size that only a row home in a major city would allow. But it was enough for them to plant small flowers and occasionally chase away squirrels. Her grandmother, who was diagnosed with dementia, continued to show an interest in plants and nature even as her symptoms progressed. Though at the time I did not think much of her interest in nature, I pondered more on the thought as I began working with people living with dementia and organizations that served them.

Though I was unfamiliar with the relation between nature and dementia, the rest of the research world had not been. In 2016, a study was done to develop a person-centered approach to creating nature activities for people living with dementia. The researchers had four research questions for participants:

- Which aspects of being in nature or outdoor spaces do people with dementia find important for their quality of life?

- What types of activities in nature do people with dementia prefer?

- What tool can be developed to support the execution of nature activities among people with dementia living in the community and in long-term care settings in a person-centered way

- Do people with dementia who experience behavior and mood dysregulation appreciate personalized nature activities?

- Are personalized nature activities feasible according to professionals in care practice?

From the first question, they identified eight key themes: pleasure, relaxation, feeling fit, enjoying the beauty of nature, feeling free, the social aspect of nature, feeling useful, and memories. The researchers then developed nature activities “according to the personal wishes, needs, and experiences of people with dementia.” They noted that participants in the pilot study “showed high levels of positive behaviors and low levels of negative behaviors.”

Some of these themes are echoed in other writings about nature and dementia. An article from the Dementia Services Development Centre discusses the importance of getting outside for people living with dementia. They even distinguish walks in nature from walks indoors by noting that “walks outside, ‘green’ walks, reduce stress levels and increase people’s self esteem, allowing for activity and sociability as well as contact with nature – whereas a walk in a shopping mall may show no improvement in mood at all.”

During social isolation and COVID-19, places like the Morris Arboretum are offering ways for people to learn about and connect with nature from home. The vision of the Morris Arboretum is to act as a resource for “understanding of the importance of plants to people, in a biological, cultural, historical and aesthetic context.” To act on this mission, they are offering several videos and blog posts on planting and detecting different types of plants in nature. They also are offering content on their social media platforms like this morning contemplation video to help those at home to relieve anxiety and stress while at home and separated from nature.

Activities in nature can act as a source of peace and engagement for those living with dementia. Through our ARTZ in the Neighborhood programs, we hope to hear from our community the types of activities and places that give them joy.